Call us toll-free: 800-878-7828 — Monday - Friday — 8AM - 5PM EST

By Jordan Rau for Kaiser Health News

Many small, rural hospitals are having a hard time fitting into new accountability standards of the Affordable Care Act. Critical-access hospitals aren’t yet part of Medicare’s pay-for-performance plan, and Congress never provided money for testing how to tie bonuses and penalties to hospital performance.

Crawford Memorial Hospital, in rural Robinson, Ill., is the only hospital for miles around.

Just like elsewhere, Crawford’s doctors deliver babies, perform routine operations and see thousands of patients in the emergency room.

But Crawford, along with one-quarter of the hospitals around the country, is being left out of some of the biggest shifts in American health care initiated by the Affordable Care Act. These changes are aimed at bringing accountability to hospitals by linking Medicare payments to the quality of their care. They also are encouraging hospitals to monitor patients’ health so doctors and nurses can intervene before problems become acute.

The Department of Health and Human Services has not yet incorporated the 1,256 primarily rural, “critical access” hospitals such as Crawford into Medicare’s pay-for-performance programs. With no more than 25 beds, these hospitals are generally located in isolated areas, making them the only acute-care option for local residents. Medicare repays them their cost plus 1 percent, more than it pays other hospitals, to ensure they do not close.

While some of the facilities deliver exemplary care, a study published last year by Harvard School of Public Health researchers found that death rates at critical access hospitals in 2010 were higher than at other small, rural hospitals and the industry overall.

The health law required the government to start testing how to provide bonuses and penalties to critical access hospitals based on their quality by 2012. But Congress never provided any money.

Other Medicare efforts to improve care also are not making major inroads among rural hospitals.

Fewer than 1 in 20 critical access hospitals are participating in accountable care organizations, or ACOs, in which hospitals and doctors coordinate services with the promise of bonuses from Medicare if they deliver care more efficiently. Another project, to test new ways to deliver rural health care, is limited to five states, and the selection of participants has not been announced even though the deadline for applications was in May.

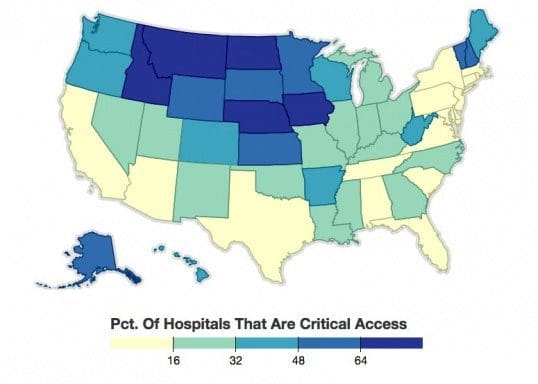

Critical Access Hospitals In States

A quarter of the nation’s hospitals are designed as “critical access” facilities, generally because they are the only hospital in an area. Medicare pays them more generously than other hospitals, but they have been left out of many of the changes spurred by the Affordable Care Act. This map shows what percentage of hospitals in each state are critical access.

“It’s very unfortunate that critical access hospitals continue to be exempt from all the new policies aimed at improving quality and safety at hospitals in America,” said Leah Binder, CEO of The Leapfrog Group, a nonprofit that evaluates hospital performance for consumers and employers. “If you live in a rural community and you are dependent on a critical access hospital, the federal government has abandoned you.”

Medicare officials declined to discuss the issue but said in a written statement that their authority in many areas is limited by Congress.

Some rural health care leaders say they are rankled at being marginalized and concerned that they could be left behind as reforms spread.

“I do not want to see my hospital on the sidelines,” said Don Annis, chief executive of Crawford, which serves people near the Indiana border about four hours south of Chicago. “I want us to be prepared for this.”

Instead, Crawford is part of the Illinois Critical Access Hospital Network, which is developing its own ACO.

“That’s a much better environment to be in,” he said.

Critical access hospitals have other reasons to be leery of the new incentives, as they are not eager to risk losing money if they perform poorly. “Providers are reluctant when they have fragile financial status to participate in the program,” said Ira Moscovice, director of the University of Minnesota Rural Health Research Center. But, he said, “I think it’s rather shortsighted to think you’re going to be excluded from this.”

Forty-five states have designated some of their hospitals as critical access under a 17-year-old program that helped stop a wave of closings in rural communities. There are 50 critical access hospitals in Illinois and even more in Texas, Wisconsin, Nebraska, Kansas, Minnesota and Iowa.

The health law excused critical access hospitals from inclusion in the early years of Medicare’s pay-for-performance incentives. They are exempt from fines levied against hospitals with a large number of patients who return within 30 days, as well as penalties or bonuses based on patient satisfaction reviews and hospital death rates.

Congress gave these hospitals a reprieve because of the difficulty in bringing them into the pay-for-performance programs. Many of the ways Medicare is measuring hospital quality require enough cases to be reliably analyzed, but these tiny hospitals often don’t have enough heart attack patients, for instance, to estimate death rates. Other measures look at surgical practices, but critical access hospitals often ship those patients to bigger institutions. Experts have come up with customized measures that could be used to judge rural hospital quality, such as the time it takes to evaluate a patient in the emergency room.

Other hospitals are required to report quality scores on Medicare’s Hospital Compare website. Critical access hospitals can do that voluntarily, but many do not. Data show that only about one out of three critical access hospitals report their emergency room quality measures, even if just to say they did not have enough cases to evaluate. Brock Slabach, an executive at the National Rural Health Association, said the participation level is laudable given that it is voluntary and that the measures are only a few years old.

“Ten years ago, I think the majority of folks would be opposed,” Slabach said. “Now they’ve resigned themselves to the fact that this is going to be inevitable.”

Tim Size, executive director of the Rural Wisconsin Health Cooperative in Sauk City, a collaborative of 39 hospitals, said it would be a mistake for rural hospitals to avoid the public reporting and payment changes that other hospitals are adopting. “It reinforces a bias that rural hospitals are backwater and you wouldn’t want to go there,” he said.

Some critical access hospitals have found ways to get involved in new payment arrangements. The Wisconsin hospitals in Size’s cooperative have contracts with private insurers that provide financial incentives for quality. In Batesville, Ind., which lies between Indianapolis and Cincinnati, Margaret Mary Health joined six hospitals and a group of clinics around the country to form a virtual ACO with enough patients to qualify for the Medicare ACO program.

Margaret Mary President Tim Putnam said the effort has had some early success. The ACO discovered that some patients take more than 20 medications, which prompted the hospital to alert doctors and pharmacists to make sure none is duplicative or interacts poorly. “We have tried to move from the place you go when you’re sick to the place that’s going to help you stay well,” Putnam said.

Medicare says 59 critical access hospitals are participating in 18 of 338 ACOs. Lynn Barr, who runs the National Rural ACO consortium in Nevada City, Calif., said, “The whole world is moving on and rural is really being left behind.”

In Robinson, Crawford was twice approached by a large hospital system based in Indianapolis that was creating its own ACO, Crawford CEO Annis said. Though Crawford was ahead of many hospitals in establishing the prerequisites for such partnerships, such as having electronic medical records, the hospital declined the offer, Annis said.

“It’s a good system, but would we have a say in determining our future?” he said. “We don’t just want to be on the bus; we want to help drive the bus.”

Instead, Crawford is part of the Illinois Critical Access Hospital Network, which is developing its own ACO. “That’s a much better environment to be in,” he said.

Crawford reports results of its patient surveys, which show better marks than the average hospital in every category except noise level at night. Crawford does not report its emergency room wait times, or the average time it took to transfer a heart attack patient needing specialized care to another hospital. Annis said the state does not require critical access hospitals to report those measures, but it may do so in the future.

“We’re a Lilliputian health system,” he said. “We do very well. We take great pride in our scores.”

As other hospitals change, Crawford needs to change too, he said. “We could be threatened if we don’t position ourselves well,” he said.